The Great Divergence: A Strategic Analysis of Marketing Philosophy and Execution in Western and Chinese Markets

- On December 4, 2025

- chinese marketing, marketing philosophy, western marketing

Introduction

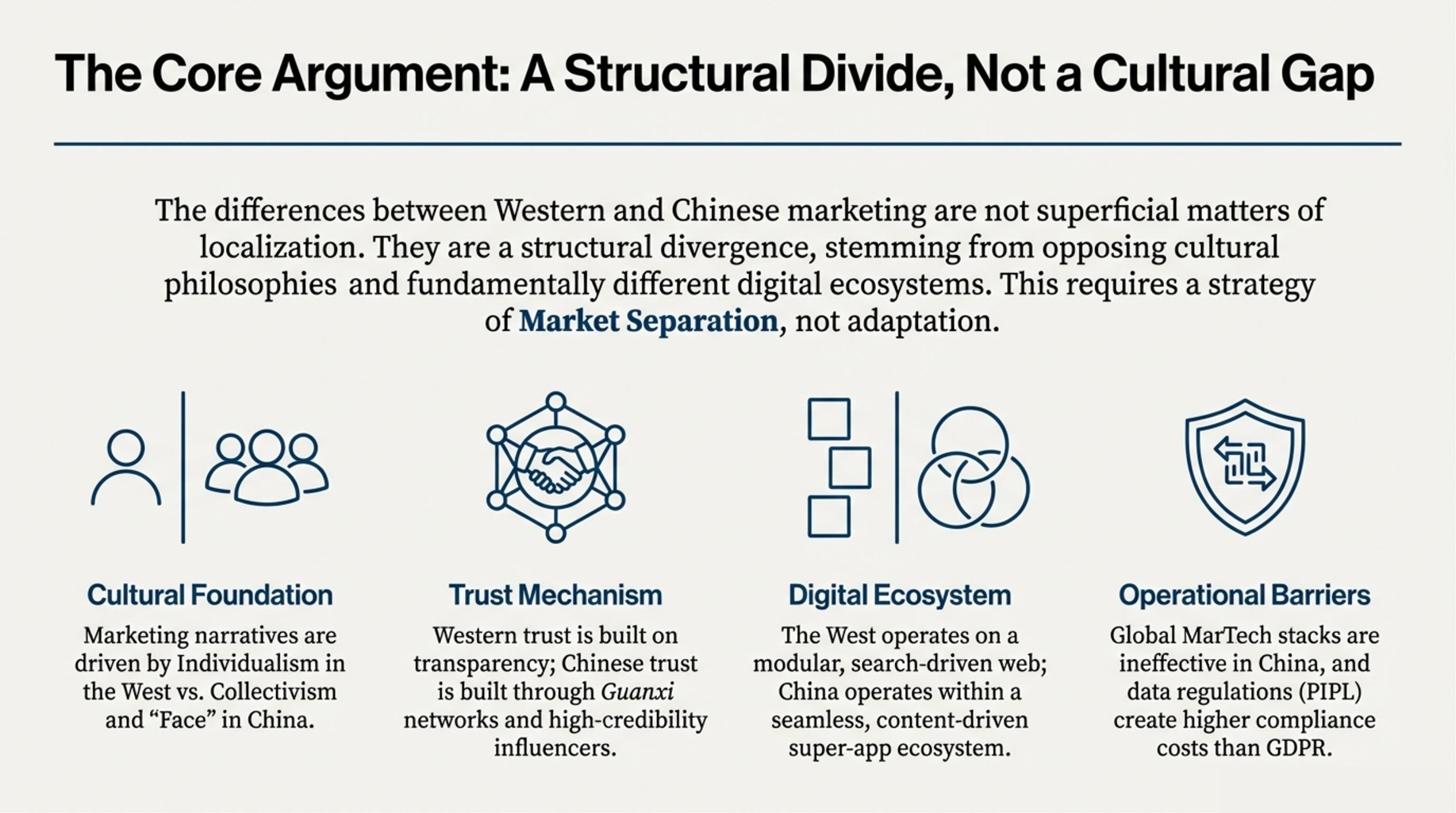

For Western business operators and marketing managers, the Chinese market presents a paradigm unlike any other. The differences between Western and Chinese marketing are not superficial matters of language or channel choice, but are fundamental, structural divergences rooted in deep-seated culture, distinct digital infrastructure, and a unique regulatory philosophy. To navigate this landscape effectively, it is critical to understand the four core pillars of this divergence: the cultural foundations that shape consumer psychology, the unique mechanisms for building brand trust, the integrated digital ecosystems that define the consumer journey, and the hard operational barriers that necessitate a separate strategic approach. This report will analyze these pillars to demonstrate that succeeding in China requires abandoning any notion of a universal marketing model. Instead, it demands a dedicated “market separation” strategy, treating China not as a localized extension of a global plan, but as an entirely distinct commercial universe.

1. The Cultural Bedrock: Why Marketing Philosophies Diverge

To understand the tactical differences in marketing between the West and China, one must first grasp the foundational cultural values that shape consumer psychology and societal norms. These values are not abstract concepts; they are the invisible architecture guiding how consumers perceive brands, make decisions, and respond to marketing messages. This section deconstructs the core cultural codes of Individualism versus Collectivism and the critical concept of “Face,” which dictate the narratives that resonate—or risk catastrophic failure—in each region.

1.1. Individualism vs. Collectivism: The Foundational Split

Leveraging Hofstede’s seminal cultural dimension theory, the primary schism between Western and Chinese marketing philosophy can be traced to the opposing values of individualism and collectivism. This is not merely a preference but a fundamental organizing principle of society.

| Western Individualism | Chinese Collectivism |

| Focus on Self: Emphasizes personal achievement, self-realization, independence, and individual choice. People are expected to make decisions based on their own thinking and needs. | Focus on Group: Rooted in Confucianism, it emphasizes group harmony, family hierarchy, and the prioritization of societal or national interests over individual gain. |

| Marketing Narrative: Appeals to uniqueness, freedom, self-improvement, and personal success. “Do your own thing” and “Be different” are powerful motivators. | Marketing Narrative: Must resonate with collective identity, social approval, and group goals. Messages that align with family responsibility or community honor are more effective. |

| Social Structure: Characterized by nuclear family structures and a more fluid relationship between ingroups and outgroups. | Social Structure: Built on extended family units and strong ingroup-outgroup distinctions. One’s place in life is socially determined and respected. |

While Chinese culture is foundationally collectivist, some studies have observed a high prevalence of individualistic themes in advertising, reflecting the market’s complex, transitional nature.

1.2. The Concept of “Face” (面子) and Its Impact on Brand Risk

A critical extension of collectivism is the social concept of “Face” (miànzi), which can be defined as an individual’s or group’s reputation, prestige, and social standing. This concept creates a cultural hypersensitivity to criticism, public embarrassment, and perceived slights, turning brand missteps that might be minor in the West into collective insults in China.

This dynamic dramatically elevates brand risk. Cultural insensitivity is not just a marketing blunder; it is an offense to the national “face” that can trigger extreme “cancel culture” and severe commercial consequences, representing an existential threat to a brand’s market presence.

- Dolce & Gabbana Scandal (November 2018): An advertising campaign featuring a Chinese model struggling to eat Italian food with chopsticks was perceived as condescending and racist, causing a catastrophic consumer boycott from which the brand is still recovering.

- Xinjiang Cotton Controversy (2021): Western apparel brands like H&M and Nike faced widespread boycotts after expressing concern over alleged human rights violations in Xinjiang, a statement viewed by Chinese consumers as an attack on the nation’s integrity.

1.3. Generational Nuances and the Rise of Guochao (国潮)

A common misconception is that younger Chinese generations, born after the 1980s and raised in a more globalized China, are simply “Westernized.” While academic studies confirm that these younger consumers exhibit more individualistic traits than their parents, they are still significantly less individualistic than their American counterparts and operate within an overarching collectivist framework.

The most potent manifestation of this is the guochao (“national wave”) trend, where homegrown brands have gained immense popularity by blending modern aesthetics with traditional Chinese culture. This is not just a preference for local brands, but an expression of collective national pride and a method of building national “Face,” making it a powerful extension of the collectivist cultural bedrock.

The strategic implication for Western brands is clear: directly transplanting Western individualistic narratives of rebellion or pure self-expression is a high-risk strategy. Instead, brands must frame modern values within a context that resonates with collective identity. Self-expression, for instance, is more effectively positioned as a way to contribute to a vibrant, modern Chinese culture rather than as an act of breaking away from it.

These foundational cultural differences directly shape the fundamental mechanisms of how brands build the most crucial asset of all: consumer trust.

2. The Architecture of Trust: Relationships vs. Transparency

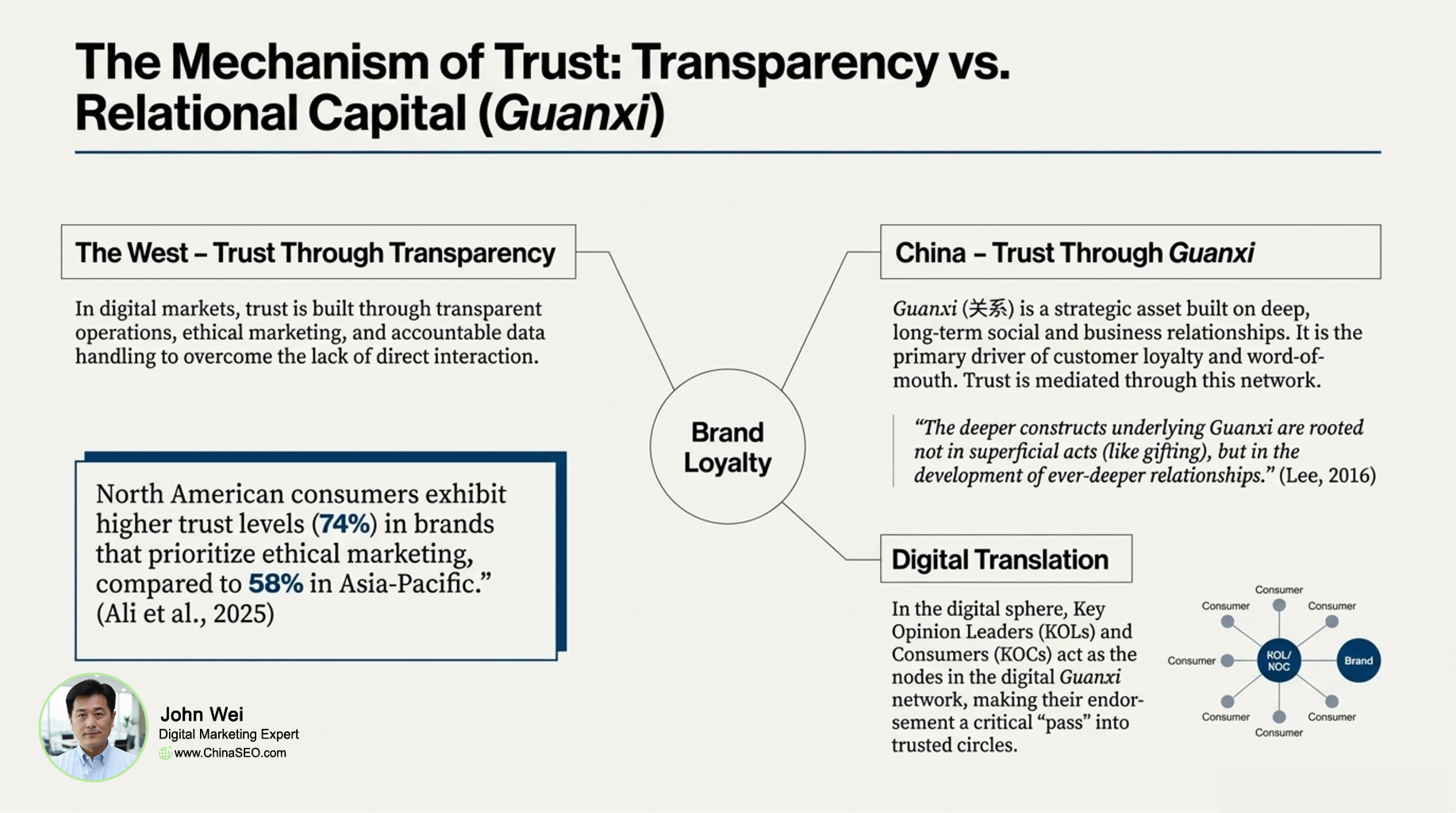

The methods for building consumer trust diverge as dramatically as the underlying cultures. In the West, trust is often an institutional construct built on transparency and ethical accountability. In China, it is a relational asset cultivated through personal networks, a concept known as Guanxi, which has been powerfully digitized in the modern influencer economy.

2.1. The Western Model: Institutional Trust Built on Transparency

In Western digital markets, the lack of direct physical interaction between a brand and its customers necessitates a strong emphasis on institutional trust. Credibility is established through transparent operations, clear data privacy policies, ethical advertising, and demonstrated Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Research confirms this approach is highly effective, with one study finding that 74% of North American consumers exhibit high trust levels in brands that prioritize ethical and transparent marketing practices. Brands are expected to be open, honest, and accountable to earn consumer confidence.

2.2. The Chinese Model: Relational Trust Built on Guanxi

In China, trust is fundamentally relational and built through Guanxi—a strategic asset based on a network of mutual trust, reciprocal favors, and interpersonal connections. This is not simply networking; it is a complex social system built on three core pillars:

- Ganqing (感情): Long-term affection and shared feelings between individuals.

- Renqing (人情): The obligation of interpersonal give-and-take.

- Xinren (信任): Interpersonal trust and reliability.

Critically, successful Guanxi is rooted not in superficial acts like simple gift-giving, but in the development of ever-deeper relationships through sustained social and business-based transactions. In the digital age, this system has been scaled and digitized. The role of the trusted intermediary, once a physical person in one’s network, is now primarily played by online influencers who act as the gatekeepers to consumer trust.

2.3. The Dominance of the Influencer Economy: KOLs and KOCs

The power of influencer marketing in China is unparalleled, serving as the digital extension of Guanxi. This is the direct digital manifestation of a trust model where consumers place faith in a trusted intermediary rather than directly in the institution. The data is stark: 74% of Chinese consumers make purchasing decisions based on influencer recommendations, compared to only 30% globally. This makes influencer partnerships not just a tactical choice, but a foundational requirement for building trust. The ecosystem is dominated by two key types of influencers:

| KOLs (Key Opinion Leaders) | KOCs (Key Opinion Consumers) |

| Celebrities, experts, or top-tier creators with very large follower bases (often in the millions). | Everyday consumers or niche enthusiasts with smaller, but highly engaged and loyal communities. |

| Function: Ideal for generating mass awareness, brand visibility, and driving large-scale campaign reach. Their authority lends credibility to new product launches. | Function: Powerful drivers of trust and conversion due to their authenticity and peer-to-peer relatability. Their reviews are perceived as genuine and unbiased. |

A sophisticated China strategy demands a hybrid approach, using KOLs for broad-stroke brand announcements and KOCs for building deep, authentic trust and driving conversions at a community level. This combination effectively balances reach with credibility.

This modern architecture of trust, built on digital relationships, functions within a unique and highly integrated set of platforms, creating a digital ecosystem that is structurally different from its Western counterpart.

3. The Digital Divide: Contrasting Ecosystems and Consumer Journeys

The digital landscapes of the West and China are not just different; they are structurally opposite. While the West operates on a modular, search-driven model with specialized platforms, China is dominated by integrated, content-driven “super-apps.” This fundamental difference has completely reshaped the consumer journey, making Western marketing funnels largely irrelevant in the Chinese context.

3.1. West vs. China: A Tale of Two Internets

- The Western Model (Modular & Search-Driven): This is a fragmented ecosystem where consumers actively move between specialized platforms to complete tasks. A typical journey involves using Google for search and discovery, Meta (Facebook/Instagram) for social interaction, and Amazon for commerce. The initial consumer action is often an active, intentional search for a product or information. Brands focus on optimizing their presence on each separate platform to guide the user through a multi-step funnel.

- The Chinese Model (Integrated & Content-Driven): This is a seamless ecosystem built on “super-apps” like WeChat and Douyin (China’s version of TikTok), which integrate social networking, content consumption, payments, and e-commerce into a single, unified experience. Consumers are often led to purchases passively and impulsively through engaging content streams, such as short videos and livestreams. The path from discovery to purchase is often instantaneous, with no need to ever leave the app.

3.2. Live Commerce: A Case Study in Market Divergence

The dramatic difference in digital ecosystems is best illustrated by the maturity gap in live commerce. Data from McKinsey highlights a chasm between China’s sophisticated, mainstream adoption and the West’s nascent experimentation.

- Market Maturity: Live commerce is a deeply embedded consumer habit in China. 57% of Chinese users are veterans who have been using the format for over three years. In stark contrast, only 5-7% of users in the West have the same level of experience, with the vast majority being recent newcomers.

- Participation Frequency: The format is a regular part of life for Chinese consumers. An overwhelming 87% of Chinese users participate in live commerce events monthly, compared to just 43% in the United States.

- Consumer Motivation: The reasons for engagement are fundamentally different. Western users primarily view live commerce as “fun” or entertainment. Chinese users, however, are driven by highly functional reasons, such as accessing exclusive deals and promotions (cited by 56%), connecting with their favorite brands, and discovering exclusive products.

- Conversion Efficiency: The integrated nature of China’s super-apps creates a frictionless path to purchase. This seamless in-platform checkout functionality helps live commerce achieve up to ten times higher conversion rates than conventional e-commerce, turning passive viewing into immediate sales.

This data illustrates that live commerce is not merely a sales channel in China, but a high-frequency, impulse-driven consumer habit that demands extreme supply chain agility and real-time inventory management—a stark contrast to its status as a novelty entertainment format in the West. This integrated user experience is made possible by a distinct set of technical and regulatory systems that reinforce the divide between the two markets.

4. Operational and Regulatory Realities: The Great Firewall of Marketing

The philosophical and digital divergences between Western and Chinese markets are reinforced by hard operational and regulatory barriers. These are not minor hurdles but formidable walls that render global marketing strategies and technologies ineffective. Western brands must contend with a completely separate technology stack and a far stricter data compliance regime.

4.1. The Ineffectiveness of Global MarTech Stacks

According to a Forrester report, standard global Marketing Technology (MarTech) stacks from vendors like Adobe, Oracle, and Salesforce are fundamentally unsuited for the Chinese market. This failure stems from several core issues:

- Lack of Ecosystem Integration: These platforms lack the deep, native integration required to operate within China’s super-app ecosystem, especially WeChat, which is central to customer relationship management.

- Outdated Design Philosophy: Global MarTech tools are predominantly designed for a PC-centric world focused on website and email marketing. This model is obsolete in China’s mobile-first market, where such channels are secondary.

- Operational Disruption: The “Great Firewall” and stringent data localization regulations cripple the performance and functionality of platforms hosted outside of China, making them unreliable and non-compliant.

The strategic imperative is clear: the only viable solution is for brands to build a separate, localized MarTech stack from the ground up, utilizing Chinese vendors who design for the local ecosystem.

4.2. Navigating Data Privacy: PIPL’s Stricter Mandates

China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) creates a data privacy environment that is, in several key aspects, stricter than the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This imposes significant operational complexity and higher compliance costs.

| Compliance Element | PIPL (China) | GDPR (EU) |

| Legal Basis for Processing | Primarily relies on explicit, unbundled consent. Critically, it does not recognize “legitimate interest” as a legal basis for data processing. | Allows for six lawful bases for processing, including “legitimate interest,” which provides organizations with more operational flexibility. |

| Consent Requirements | Requires separate, specific consent for processing sensitive data and for cross-border data transfers. Pre-ticked boxes or bundled consent are invalid. | Consent must be unambiguous and freely given but is one of several potential legal bases. |

| Data Localization | Mandates that personal data collected from Chinese users be stored on servers within China for businesses meeting certain thresholds, particularly those deemed critical information infrastructure operators. | Does not require data localization but restricts transfers to countries without an “adequate” level of data protection. |

4.3. The High Stakes of Content Compliance

China’s advertising laws are exceptionally strict and prescriptive, leaving little room for the creative ambiguity often employed in Western marketing. The risks of non-compliance are severe, ranging from fines to catastrophic public backlash.

- Superlatives are Prohibited: The law explicitly forbids the use of absolute terms like “best,” “first,” or “most effective” in advertising unless backed by official, verifiable proof.

- Strict Red Lines on Sensitive Topics: The legal and cultural red lines around content involving political figures, religious themes, and national symbols are absolute and unforgiving.

- Existential Brand Risk: Beyond legal penalties, the collectivist culture and the concept of “face” mean that even a minor creative misstep can be perceived as an insult to the nation, triggering immediate, widespread consumer boycotts that can become brand-ending events.

These operational realities demand that Western brands treat the Chinese market as a distinct entity, leading to a set of clear strategic imperatives.

5. Strategic Imperatives for Western Brands

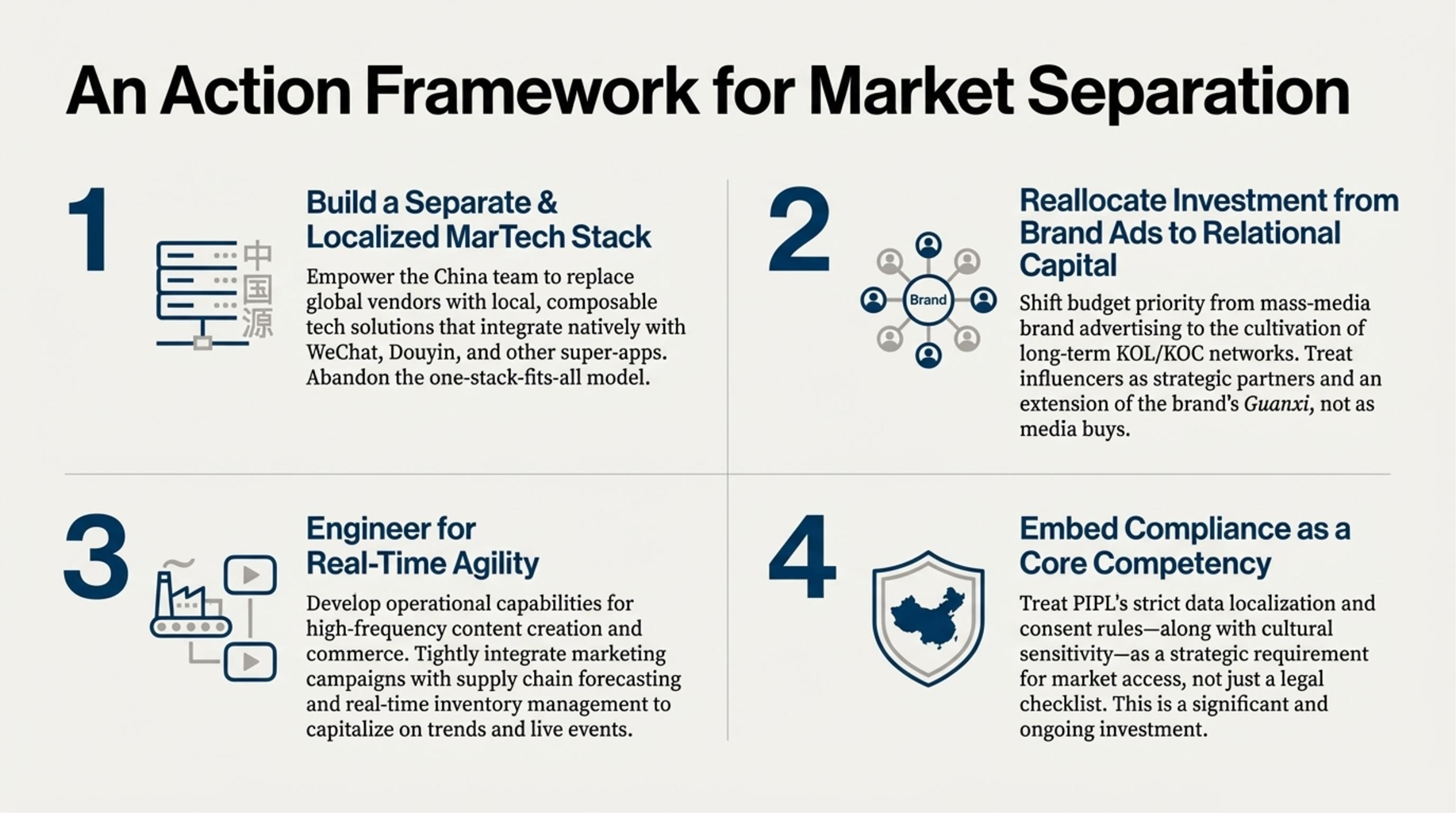

The analysis presented in this report leads to an unavoidable conclusion: success in China is contingent on treating it as a unique market requiring a dedicated, ground-up strategy, not merely a “localized” version of a global template. The structural divergences in culture, trust, technology, and regulation are too profound to be bridged by superficial adjustments. Western brands must therefore adopt a new set of strategic imperatives to compete and thrive.

1. Adopt a “Market Separation” Strategy Brands must abandon the pursuit of a unified global MarTech stack and operating model. The technical and regulatory barriers are insurmountable. Instead, empower China-based teams with the autonomy and resources to build an independent, localized technology infrastructure. This means partnering with Chinese vendors to assemble a MarTech stack tailored specifically to the super-app ecosystem, enabling deep integration with platforms like WeChat and Douyin.

2. Shift Investment from Brand Equity to Relational Capital Reallocate marketing budgets to reflect the architecture of trust in China. Move away from heavy spending on traditional, brand-building advertising designed to appeal to individuals. Instead, focus investment on the sustained cultivation of digital Guanxi. Treat Key Opinion Leader (KOL) and Key Opinion Consumer (KOC) partnerships not as one-off campaigns, but as long-term investments in relationship management and relational capital. This is how trust is built and maintained.

3. Build for Real-Time Agility The Chinese market operates at a speed and frequency unmatched in the West. The rapid trend cycles and the high-frequency, impulse-driven nature of live commerce and social selling demand extreme operational agility. Marketing, content creation, and supply chain structures must all be designed to respond in real-time. This requires local teams capable of rapid decision-making and execution, unencumbered by slow-moving global approval processes.

4. Integrate Compliance as a Core Competency The stringent requirements of PIPL and content regulations should not be viewed as mere legal obstacles, but as a strategic moat. Mastering these complex rules creates a significant competitive advantage by filtering out less committed or less prepared rivals. Brands that build deep expertise in local compliance can operate with greater confidence and stability. This requires framing compliance not as a cost center for the legal department, but as a core competency integrated directly into the marketing and operational strategy.

Unlock 2026's China Digital Marketing Mastery!

Unlock 2026's China Digital Marketing Mastery!